Pair up with one other classmate. Exchange rough drafts with them, and answer the following questions about your partner’s draft on a sheet of paper. No need to copy down the questions themselves; just write your answers to the questions. When you and your partner are both done writing, take five to ten minutes to run through what you’ve written and discuss your advice for each other. You’ll show your answers to me at the end of class.

- Does your partner’s paper provide a solid introductory paragraph? In particular, does your partner avoid the temptation to start off too generally, for example by talking about all of human nature or all of advertising throughout history?

- Does your partner provide a clear, identifiable thesis statement at the end of their introductory paragraph? If you can’t find your partner’s thesis statement, try to come up with a thesis statement for them that reflects the analysis in the rest of the paper. If there is a clear and identifiable thesis statement, is it specific enough? Does it identify the ad’s main persuasive goal and the dominant strategies it’s using to achieve that goal? Alternatively, your partner’s thesis statement might run into the opposite problem: trying to fit too many bits of specific information into one sentence. This results in a wordy and overly long thesis statement. If that’s the case, help your partner break up that single overly long sentence into two shorter and clearer sentences. See http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/thesis-statements/ for a little more guidance on thesis statements, as well some examples. e.g. Through its ____ and ____, this ad attempts to _(think not only about the basic exigence–the need to sell whatever product–but also any constraints or “micro” exigences the ad is responding to here)__.

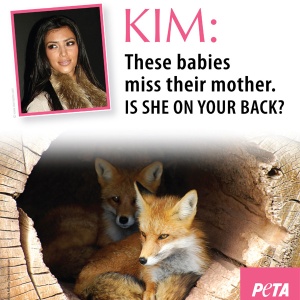

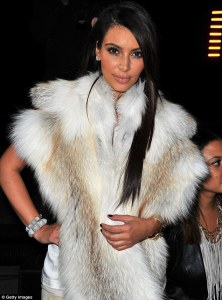

- Does your partner include enough description of the ad’s visual, textual, and/or sonic features? By “enough,” I mean enough so that readers who have not seen the ad understand what happens in it.

- Does your partner adequately explain the effect the ad has on its audience, focusing on the rhetorical appeals (ethos, pathos, and/or logos)? If not, offer suggestions for improvement.

- Does your partner adequately explain ad’s rhetorical situation, focusing on its explicit or implicit target audience(s), its exigence, and any constraints it appears to be taking into account? If not, offer suggestions for improvement.

- Did any argument or analysis in your partner’s paper seem unwarranted or exaggerated (in other words, did you think your partner was “jumping to conclusions” at times or not providing enough evidence for his/her claims)? If so, explain why.

- Does each body paragraph have a clear topic sentence that announces the specific focus of that paragraph? If not, offer some detailed suggestions for revision.

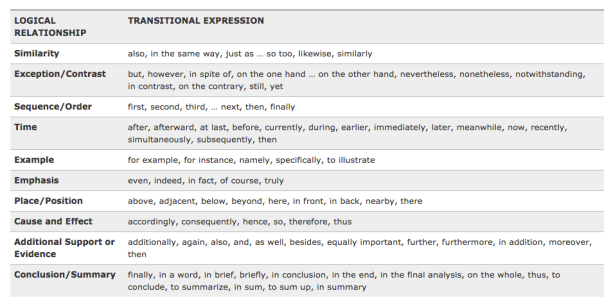

- Does each body paragraph transition from the previous body paragraph in a smooth and logical manner using a clear transitional device? If not, offer some detailed suggestions for revision.

- On the sentence-level, did you find the paper to be well written? Does it contain poor grammar? Is it unnecessarily wordy at times? If so, offer some detailed suggestions for revision.

- What, in your opinion, is the strongest part of this paper? What is the weakest?