Today, we get to define rhetoric. What’s rhetoric?

In our reading, Aristotle defines rhetoric as “the faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion.”

Persuasion is the key word there. Any idea what Aristotle means?

What is persuasion in the first place?

What are some common situations in which we find ourselves needing to persuade others, or in which we find ourselves being persuaded by others?

Even more so than in Aristotle’s age, persuasion in our contemporary age is ubiquitous–it is everywhere constantly.

In their book The Age of Persuasion: How Marketing Ate Our Culture, Terry O’Reilly and Mike Tennant make precisely this point. They write:

Had you stumbled upon this planet in any other era, you might have concluded that we lived in an age of stone or bronze, an ice age, an age of reason, or an age of enlightenment. But today? You couldn’t help but conclude that we live in an age of persuasion, where people’s wants, wishes, whims, pleas, brands, offers, enticements, truths, petitions and propaganda swirl in a ceaseless, growing multimedia firestorm of sales messages. (xiii)

We are constantly bombarded by attempts to persuade us–by advertisements (which persuade us to buy a product), by politicians (who persuade us to vote a certain way), and even by countless fiction films and television shows (e.g. a romantic comedy persuading us to feel particular feelings about an entirely fictional character or narrative).

Why does this matter for Comp 105?

For starters, our first major writing assignment–Project 1–is arhetorical analysis. To do a rhetorical analysis–to, as Aristotle puts it, “observ[e] in any given case the available means of persuasion”–means to observe, uncover, and reveal exactly how these different media forms (e.g. advertisements, political statements, movies, and so on) are attempting to persuade their audience to do a certain action, think a certain thought, or feel a certain feeling.

Why do we do rhetorical analysis in a writing class? Because, by analyzing and decoding how rhetoric and persuasion work in other people’s arguments, you become better at using rhetorical or persuasive strategies in your own argumentative writing. (More on that later when we get to Projects 2 and 3; it’s with those assignments that we’ll begin to pivot from just analyzing other people’s arguments to making our own arguments.)

The first step in learning how to do a rhetorical analysis of an argument is to learn some useful rhetorical concepts that you can apply in your analyses. Today, we’re going to look at one set of those concepts:

The Three Rhetorical Appeals

- Ethos (Credibility): persuasion based on the character, expertise, or ethics of the speaker; convincing the audience that the author or maker of the text shares their values and way of life. Here’s Aristotle on ethos:

Persuasion is achieved by the speaker’s personal character when the speech is so spoken as to make us think him credible. We believe good men more fully and more readily than others … It is not true, as some writers assume in their treatises on rhetoric, that the personal goodness revealed by the speaker contributes nothing to his power of persuasion; on the contrary, his character may almost be called the most effective means of persuasion he possesses.

- Pathos (Emotion): persuasion that manipulates or exploits an audience’s emotions. Here’s Aristotle on pathos:

Secondly, persuasion may come through the hearers, when the speech stirs their emotions. Our judgements when we are pleased and friendly are not the same as when we are pained and hostile. It is towards producing these effects, as we maintain, that present-day writers on rhetoric direct the whole of their efforts.

- Logos (Logic): persuasion based on logical reasoning and often quantifiable grounds and evidence. At its most fundamental level, logos refers to the internal structure or organization of an argument. For instance, some of you in your Blog Post 1 might have noted that you’re good at coming up with ideas for essays, but have trouble organizing them into a logical structure that the reader can follow. What you’re looking for is logos. Here’s Aristotle on logos:

Thirdly, persuasion is effected through the speech itself when we have proved a truth or an apparent truth by means of the persuasive arguments suitable to the case in question.

Let’s look at these three appeals in more detail now, with examples.

Logos

Good logic can indeed be thought of as crucial to being persuasive, a kind of ideal state for any argument and for public life in general. It’s good to be logical, and we should all aspire to make logical arguments.

The reality, however, is that we certainly don’t–indeed, we can’t–always think or communicate with good, consistent logic. As the following video demonstrates, human nature is such that we can’t help but make mistakes, we abuse good logic, we have biases, we lie, and so on:

Rhetorical analysis makes you think not only about the solidness or soundness of a logical claim, but also–more importantly–about the underlying problems with logic. We will work our way toward understanding how logos plays a part in forming smart larger arguments, but today we should emphasize that rhetorical analysis ‘reads’ for more than fully-fledged, logically clear arguments–since (as you can already tell) there is much more about persuasion in society than a world of air-tight, logically bulletproof arguments.

In short, rhetoric asks us to think realistically about the good uses of logic, but also about its limitations.

For instance:

“Good logic” can be abused to support bad ideas, and we have many examples of classic satirical essays that draw on the appeal of logos to spoof how we can rationalize almost anything.

Additionally, logos is also quite persuasive when it’sincomplete. That is, much of the information we encounter in the world is given to us in a fragmented or partial form–what Aristotle, and the other ancient rhetoricians, called the enthymeme.

In Book I, Chapter 1 of the Rhetoric, Aristotle defines enthymemes as “the substance of rhetorical persuasion.” He also mentions them a great deal in our reading, Chapter 2. For example:

The enthymeme must consist of few propositions, fewer often than those which make up the normal syllogism. For if any of these propositions is a familiar fact, there is no need even to mention it; the hearer adds it himself.

An enthymeme is a claim about something, but not quite a fully fleshed-out argument. As Aristotle puts it, your average enthymeme has “fewer [propositions] than whose which make up the normal syllogism.” Smart people (people who are comfortable thinking rhetorically) always look to read arguments in terms of their component parts, and in the enthymeme, not all of these parts is made explicit to you. (This connects to logos in that logos is always about the internal structure of in argument, the relations between its component parts and how well those parts fit together.) Let’s lay out the most common component parts of an enthymeme below:

The claim

The stated reason for the claim

The unstated assumption behind the claim

Grounds or evidence supporting the claim

A fully developed, fleshed-out argument will make all of these parts explicit to its audience. Enthymemes, by contrast, are claims that come to us missing some of these component parts, but that are still undeniably persuasive to us humans. Why are they still persuasive?

Because people tend to “fill in” the blanks with assumptions, biases, or pre-conceived reasons. This is what Aristotle means, in the passage we just quoted, when he says, “if any of these [missing] propositions is a familiar fact, there is no need even to mention it; the hearer adds it himself.” Most people add or fill in these blanks automatically, without reflecting on it or thinking about it. Other people, however–people like you, who will soon be trained to think rhetorically and do good rhetorical analysis!–will take a more critical, intellectual stance toward how these blank spaces get filled during the process of persuasion.

Some famous enthymemes:

“All humans are mortal, so Socrates is mortal.”

Claim: Socrates is mortal

Stated reason: all humans are mortal

Unstated assumption: because Socrates is a human

“The glove doesn’t fit, so you must acquit.”

Build your own enthymeme:

Women should be allowed to join combat units because the image of women in combat would help eliminate gender stereotypes.

Claim:

Stated reason:

Unstated assumption(s):

Evidence:

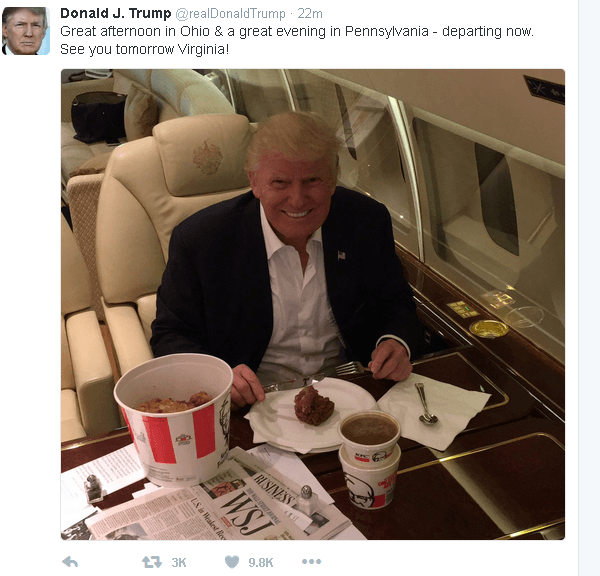

An argument in which there’s a whole bunch left unstated (and thus a good example of the sorry state of American political discourse):

“Make America Great Again”

Claim:

Stated reason (is there even one?):

Unstated assumption(s):

Evidence:

In sum, this is what I’ll mean when I ask you to analyze the logos of an argument: I am asking you to dissect and break down its logical structure, its component parts. Which of the parts are explicit and present to the audience, and which are only implied and left for the audience to “fill in”?

Pathos

Of course, being persuasive involves more than being logical. Indeed, often the most persuasive arguments are those that skip the logical details and focus instead on stirring up emotions in their audience, as this clip from Mad Men demonstrates:

How does pathos work? The following video, which presents a “Skype Laughter Chain,” offers some insight:

Emotions are contagious. Seeing someone laugh tends to make us feel like laughing in turn. Likewise, unfortunately, for seeing sad stuff:

Ethos

Ethos refers to persuasiveness derived from credibility or trustworthiness.

For example, when you eventually write a college-level research paper, you’ll build ethos or credibility by citing high-quality sources. A student whose only source is a Wikipedia article will appear significantly less credible than a student citing multiple books and scholarly articles from the University library.

Ethos is also an important factor in advertising. For example, when an actor in a pain reliever commercial puts on a doctor’s white coat, the advertisers are hoping that wearing this coat will give the actor the credibility to talk persuasively about medicines:

On the other hand, in the video below, the actor’s ethos is perfectly clear about how it’s a deceptive illusion (which ends up producing a form of pathos as a result: the emotional response of laughter):

All throughout the media, sports heroes, popular actors and actresses, and rock stars are often seen as authorities on matters completely unrelated to their talents. This is an instance of the persuasive power of image and ethos.

Ethos also has to do with something a bit more complex: something more like, shared way of life or shared worldview. Hence: