The Proposal Stasis

Last time we ended by covering the evaluation stasis. We’ll continue using the evaluation stasis today as we move to the proposal stasis. This is because proposals always imply some degree of evaluation. In order to propose a solution to some problem, you have to begin by evaluating the current state of things to show that they’re bad in some important way and in need of improvement or fixing; only then does it make sense or feel exigent to propose a solution and fix what needs fixing.

So, it’s best to think of the proposal stasis as a “proposal/evaluation” combination.

The amount of evaluating you do versus the amount of proposing you do depends on the particulars of your topic.

For example: most people in Michigan already agree that our roads are in horrible shape and in need of fixing. What people disagree about is the solution: what the best way to fix the roads is. Indeed, back in November of 2015, a roads funding bill narrowly made it through the Michigan House and Senate, and before Gov. Snyder went on to sign it, it faced a barrage of controversy:

That‘s where the exigence lies–if you wrote a paper about this issue, the exigence (the thing that would be provoking you to write) is not that people don’t get how bad Michigan’s roads are (they do), but rather that people can’t agree on how to fix them. So: if you wrote a paper about this topic, you wouldn’t need to spend much time convincing or persuading your reader that the problem exists. Instead, you would want to prioritize (i.e. spend more time and effort on) convincing them that your solution–the one you’re proposing–is the right solution, the better solution. In other words, you would want to prioritize the “proposal” side of the proposal/evaluation dynamic over the “evaluation” side (although part of making this work is, also, evaluating other people’s proposals).

Another point: the ratio of evaluation to proposal also depends on who your primary target audience is. This thing you’re evaluating might already feel like a problem to some group or even some large proportion of the general population. For instance, let’s take the controversy over the NCAA’s classification of college athletes as unpaid amateurs:

As this clip makes clear, the fact that college athletes don’t receive payment for playing probably already feels like a problem to most college athletes. And it also now probably feels like a problem to the more general group of viewers who watched this episode of John Oliver’s show Last Week Tonight when it aired on HBO. However, we run into an exigence here: these specific groups–college athletes and viewers of Last Week Tonight–would certainly be receptive audiences to a paper claiming that college athletes deserve payment, but they’re probably not the audiences best equipped to fix the problem.

Rather, the audience best equipped to fix this problem–probably the NCAA or the universities and colleges involved–might not even realize this lack of payment is a problem in the first place; or, even more complex, this best-equipped-to-fix-it audience might very well have some sense that people are mad about this lack of payment, but doesn’t fully appreciate yet–or hasn’t been persuaded yet–just how much of a problem it is, or that it’s a problem worth solving now.

In this case, you’d want to give more priority to the evaluation stasis. It would be like you’re telling this audience: listen, you at guys at the NCAA or in the college athletic department, this thingis a big problem, much worse than you think it is, so fix it, and do it now! And, by the way, here’s a possible solution I’m proposing (that’s where a little bit of the proposal stasis would come in). And so, in a paper like this, your exigence–the thing that’s provoking or bugging you enough to write–is not so much what the best solution is to treating college athletes fairly, but rather that the people in charge of how those athletes are treated don’t even recognize that there’s a problem in the first place. Here, we’d be prioritizing evaluation over proposal.

Really short group exercise

Get into groups of 3 or 4.

Groups to which I assign an odd number will brainstorm to come up with an issue that would require prioritizing evaluation over proposal. Remember, the exigence in this case is that not enough people get that some important thing is a problem in the first place.

Groups to which I assign an even number: you’ll come up with an issue in which the burden lies on the proposal side of the equation. Remember, the exigence for an issue like this resides in the fact that, while everyone agrees that this important thing is a problem, nobody can agree on how to solve that problem.

You have 15 minutes. Feel free to use the internet in your search. We’ll discuss the results thoroughly after you’re done.

Now, let’s work from your topics and try to develop them into fuller, more internally structured arguments–exactly the kind you should be shooting for with Project 3.

In particular, we’ll think about any spots or areas in which the definition or causal stases may come into play as we develop the argument.

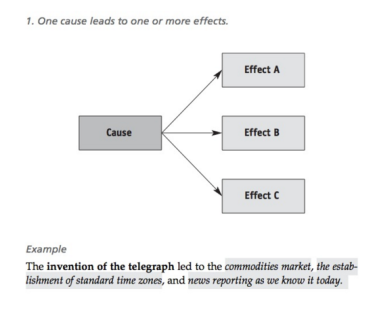

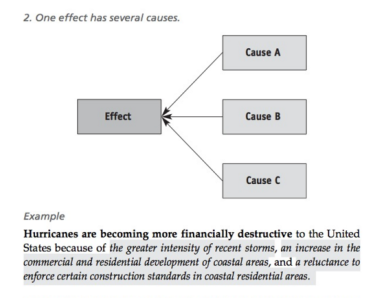

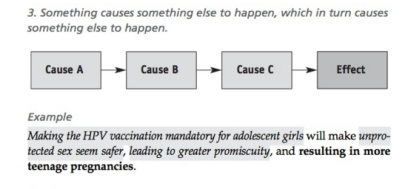

A little on the causal stasis:

Group 1: should abortion be legal–already was resolved legally (roe v wade), but is constantly re-evaluated in terms of whether it should be legal or not; defintion: what is life, when does life begin–what counts as life; what is caused by abortion remaining legal? what would be the consequence(s) if it were rendered illegal?

Group 2: anti-vaccine parents; individuals who are pro-vaccine (doctors, for instance) don’t know how to best approach anti-vaccine parents. would target doctors: your persuasive strategies have been unpersusaaive toward anti-vaccine parents–i propose in this paper a more effective strategy for chanigng anti-vaccine parents’ minds. a “Right” (legal) versus what’s in public best interest (also morality) >> cause/consequence? more strategies need to be implemented or else.. negative effects on health, or else more measles >> what are the causes for anti-vaccine attitude?

Group 3: global warming >> some people think it’s not a big deal (who are some people) >> not the majority of scientists; effects of global warming are not perceivable on a human timesecale (at least in the West, e.g. in MI); consequence = florida is underwater (sorry flordia man) consequencdes down the line; definition stasis? what is global warming–

Group 4: parking scarcity at um dearborn–people who don’t have to worry about it: deans (not lecturers), tenured faculty; define good parking (why is the parking bad; what would it look like if it was good); define different categories of parking (visitor v. faculty v. student); consequence = students for late classes, students unenrolliung out of anger at the parking situation in a moment of heated passion; why did we lose taht lot??~!? practical? aesthetics? (dont’ interfere with the campus greenspaces)

Group 5: funding for planned parenthood–target people unaware of what pp actually does and how it’s funded; what is causing this misinformation to stick, where does it come from; define: planned parenthood

Group 6: terrorism; definition: what is terrorism in the first place? cause-consequence:

Group 7: bees dying off in mass numbers–target audience = pesticide manufactuers

For next time:

Due: Blog Post 4